The white bushman, by Peter Stark

Peter Stark is the legendary white Bushman who writes about his experiences in hunting, tracking and surviving in former German South West Africa.

[...] Willie, the old Bushman, became my black father. He was much more than just a very good friend to me. I learned an immense amount from him, because even though he was "just" a simple Bushman, he was also a philosopher. Willie had phenomenal tracking abilities and knowledge of the bush. When I got to know him, he was already about 50 years old, and was born "wild" in the bush. He was a Heikum Bushman, and enjoyed enormous standing amongst the Bushman tribe as a medicine man. The West Etosha region was overgrown, sandy and as flat as a pancake. There are no mountains to help in gauging direction, only thick bushes and trees. When we began hunting together, I simply stumbled along behind Willie like a blind mole, never knowing where I was. There were three large fountains on the farm, and no fencing. The entire western boundary abutted on Etosha. This meant there was never any shortage of wildlife. Many hungry mouths needed to be fed, and so we hunted almost every week. We usually shot three animals during every hunting trip - far apart and in different directions. We then walked home, inspanned two oxen to pull a wagon, and once more ventured into the bush to load the animals. Willie always led the oxen. We often had to skirt around particularly thick bush, but nonetheless Willie always managed to head straight for the carcasses, without any hesitation or sidetracks, even though the carcasses were many kilometres apart. It was often dark before we managed to get home. I often had no clue whether I was coming or going, but I never saw Willie hesitating. It made me feel hugely inferior, and I began to ask many questions.

"Look at that tree, it grew in that particular way. Look at that palm tree, look at that little flat area, look at that crooked anthill," Willie would then explain. "Always watch your shadow, so that you know the direction you're moving in. Watch the stars at night," he would always say When I had some time to myself over weekends, I went into the bush and started practising, using Willie's methods. In this way I extended my knowledge of the bush and was able to orientate myself and determine directions, until I was able to take the lead and bring us back home safely. This proved of immense value in my later life as a game warden, particularly in parts of the park that were still completely unexplored. I always took the lead on horse patrols, when we often followed tracks through the bush for 100 to 130 kilometres every day, returning to various camps at night, and also determined our direction. I have Willie to thank for all this knowledge.

Willie's knowledge of tracking was phenomenal. At first I doubted whether he was in fact still following tracks. He walked upright and usually quite fast, and initially it seemed to me that he wasn't tracking at all. Even walking right beside him, I could often see no tracks at all, and then I would ask him if he was actually still following a trail. With the help of his little tracking stick he would then point out the tell-tale signs to me. Early on I always became very angry when we were following a lion's tracks and Willie would suddenly veer off to one side or the other simply to pick off some edible gum or fruits, or to dig up some tasty roots or tubers.

"What about the lions?" I would ask him. "They're still far away," he would reply, and Willie was always right. He never got angry, and was always ready with some carefully considered philosophy. I felt small and humble on such occasions, and kept my mouth shut. Often when I was walking behind him on a lion's tracks, I would resolve: I'm going to see the lion first today! But it was always the same: Willie stood to one side and with his stick pointed at a thicket in front of us. And there the lions were. One could often see only their paws in the long grass while they were snoozing on their backs in the shade of a tree.

When talking to Willie, he could say things which compelled you to think, or to burst out laughing. He had a tremendous sense of humour, and was always ready with a quick retort. He spoke good German, and I taught him some typical overseas German hunting practices, with all the right vocabulary. He used these words when he accompanied visiting German hunters. It always gobsmacked them to hear these words from the mouth of a Bushman. He had the most amazing stamina. I was never able to tire him out, even at his age, as I often tired out younger Bushmen, who would then lie down for a bit and later join us at camp. He could carry unbelievable masses of meat over long distances - something I could never do, or could never face. Most Bushmen are masters at this, easily outperforming bigger and stronger men.

Once a buck has been cut up, and the meat needs to be carried to a certain point, they will get hold of a makalani palm stalk (preferably) and remove the sharp points on either side of the stalk with a knife. The malakani palm stalk is then placed in the fork formed by a side branch growing from the nearest tree-trunk. The carrying-stick for the meat is evenly loaded with meat on both sides, and will hang slightly below the carrier's shoulder-line. The middle of the stick is bare, because that part will rest on the bearer's shoulders. The Bushman will then look for a second suitable stick, usually his club. When everybody is ready to go, the men will all place a shoulder under the bare part of the meat-laden branch and lift it from the tree-branch so that it rests on the Bushman's shoulder. The other stick is then placed on the unused shoulder and positioned underneath the load of meat behind the man's back. By shifting the pressure on the second stick he is able to lift the load of meat from the loaded shoulder, and this automatically spreads the weight of the meat more evenly across both shoulders. [...]

This is an excerpt from the book: The white bushman, by Peter Stark.

Title: The white bushman

Author: Peter Stark

Publisher: Protea Boekhuis

Pretoria, South Africa 2011

ISBN 978-1-86919-413-0

Softcover, 15x22 cm, 224 pages, several b/w photos

Stark, Peter im Namibiana-Buchangebot

Conservation Pioneers in Namibia

Conservation Pioneers in Namibia and stories by game rangers: a compelling and insightful read.

The White Bushman

With Peter Stark’s unique and genial narrative voice, The White Bushman presents an important cultural-historical perspective on the country that became Namibia.

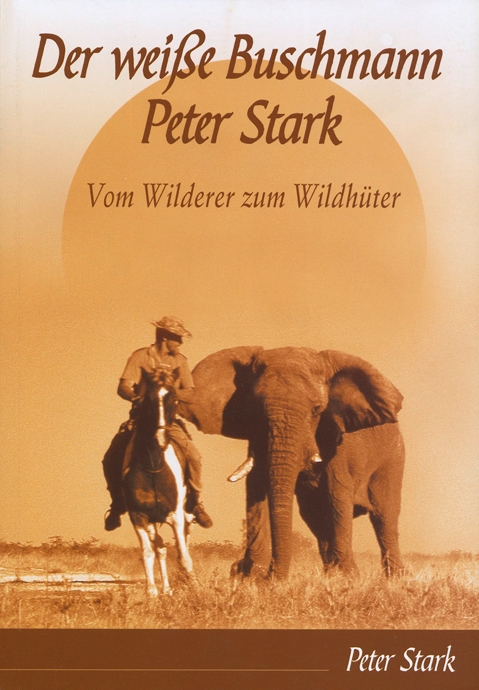

Der weiße Buschmann Peter Stark

Als weißer Buschmann wurde Peter Stark wegen seiner legendären Fähigkeiten im Busch bezeichnet. Dies ist seine Lebensgeschichte als Wilderer und Wildhüter.

Weitere Buchempfehlungen

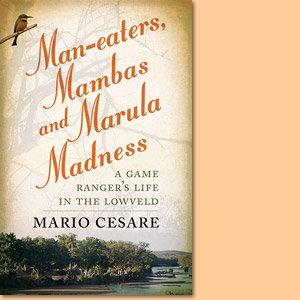

Man-eaters, mambas and marula madness: A game ranger's life in the Lowveld

Mario Cesare, in man-eaters, mambas and marula madness, decribes his life as a game ranger in the Lowveld region.