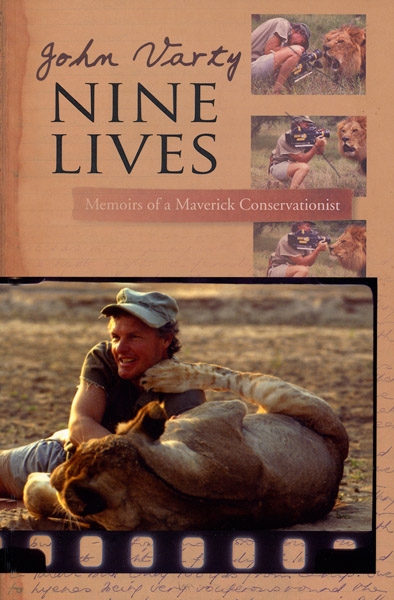

Nine Lives. Memories of a maverick conservationist, by John Varty

Nine Lives chronicles the adventures, trials, mishaps and triumphs of John Varty’s astonishing life, tracking his progression from hunter to film maker to environmentalist. This is out of the chapter The Hunter.

It is dawn in South Africa's lowveld. Reverberating across the bush is the roar of a male lion. A kilometre away, two men and a boy come to a halt. In front is a Shangaan man, a master tracker and hunter named Winnis Mathebula. Behind him stands Boyd Varty, my father, and, behind him, I stand, scared stiff. Winnis turns his head, listening, pinpointing the exact position of the roaring lion. He turns to my father: 'Xana u dawula?' (Who will be shooting?) 'Nkosana' (The boy), my father replies. Winnis turns at a right angle to the lion and moves down a game path towards a fallen tree where there is good cover for the three hunters and on which I can rest my rifle. Together we wait, the three of us huddled in the grass behind a round-leaved kiaat bush. I am in front, my father behind me, and Winnis behind him. My father whispers reassuringly into my ear, 'The lion will come down the game path.' My heart is beating uncontrollably, my hands are shaking and the barrel of the gun is rotating wildly. The lion roars again ... he is coming closer ... fear grips me. I want to say to my father, I'm scared. I don't want to hunt this lion. I want to go home/ but I can't. If I kill this lion, I will pass into manhood; it's a rite of passage, a tradition passed down in the Varty family.

Now is the moment of truth. There is no turning back. I must go through with the hunt. I must show my dad and Winnis that I am brave. I can do it. The lion appears, walking towards us down the game path, just as my father predicted. He marks his territory and ambles straight towards us. He is totally unaware that he is being watched by three humans lying in wait for him. He is magnificent, with a full black mane ... the kine. I squint down the barrel of the gun, lining up the sights on the lion. 'Wait for him to come closer!' my dad commands. The sweat stings my eyes; a fly flicks across my face. I move my hand to brush away the fly and the lion sees the movement; he raises his head. 'Now!' my dad orders, and I shoot the lion through the chest. He drops like a stone.

My dad and Winnis are elated, patting me on the back, shaking my hand. I performed in the heat of the moment - my aim was true and I delivered when it counted most. I am a man. I am just twelve years old. In a state of shock and with adrenalin pumping through my body, I move closer to examine the lion. He is in his prime, with a tawny and black mane. A few minutes ago he was roaring, marking his territory, and now he was stretched out, lifeless. The interaction was brief: we heard him roar and saw him mark territory, he walked towards us and saw us, and I shot him dead. Any chance of our ever meeting again is gone. Any chance of my ever learning anything about the life of this lion is gone. Instinctively, as I gaze at the magnificent creature, I know something is wrong.

What should be the highlight of my young life is tinged with sadness, an inexplicable feeling of loss. I keep it to myself. All around me is euphoria and celebration. Trackers and hunters arrive. My mother comes out to see the dead lion. The great Harry Kirkman, who is reputed to have hunted and killed over a thousand lions, comes to congratulate me. My status with the Shangaans is sky high; Tilu (my nickname, which means 'thunder and lightning', given to me because of my volatile temper) has killed a lion. I like what I see; I like what I hear.

My grandfather, Charles Varty, was a businessman and an extremely keen hunter who travelled all around Africa, hunting. He was very friendly with James Stevenson-Hamilton, the first warden of the Kruger National Park. In 1926, he and his business partner, Frank Unger, an equally enthusiastic hunter, were playing tennis in Johannesburg when they heard that some land just outside the Kruger National Park was up for sale. A map was delivered to them at the tennis party, on which the available land was demarcated. They decided then and there to buy two pieces of land, sight unseen, with a total area of 4000 morgen (about 3 400 hectares), paying one shilling and sixpence per morgen. They divided the land between them, and my grandfather drove in his car to the village of White River in today's Mpumalanga province, where he hired a span of oxen and a team of porters.

Guided by his map and a compass, he headed for the Sand River, which was part of the land he'd bought. He planned to make his camp there. After weeks of trekking, the porters just sat down. They went on strike, declaring that there was no river and refusing to budge. Charles, who was a skilled linguist, used his very best Zulu and the offer of more money to try to persuade them to go on. Finally, after much bargaining, they agreed to continue and, just a few hundred metres further on, they found the river. The point where he reached the river is exactly where the Londolozi camp is situated today.

My father, Boyd, used to tell me another story about his father. When my dad was a little boy, he and his father were travelling in the ox wagon. They had been delayed on their journey and it was getting late. My grandfather knew that it wasn't a good idea to pitch their tent in the dark, but he wanted to cross over a small river to pitch his camp on the other side. Although it wasn't yet dark, the sun was starting to set, so he was under some pressure. As they went down into the river bed, a male lion reared up and grabbed the front ox. The lion had been watching them from the reeds, waiting for his opportunity. Since the light wasn't great by this time, my grandfather couldn't see well enough to take a shot, so he shouted to my dad, 'Bring the light! Bring the light!' (...)

This is an extract from the book: Nine Lives. Memories of a maverick conservationist, by John Varty.

Title: Nine Lives

Subtitle: Memories of a maverick conservationist

Author: John Varty

Publisher: Zebra Press

Cape Town, 2010

ISBN 978-1-77022-132-1

Softcover, 15x23 cm, 280 pages, several colour photos

Varty, John im Namibiana-Buchangebot

Nine Lives. Memories of a maverick conservationist

Nine Lives: Memories of a maverick conservationist chronicles the adventures trials, mishaps and triumphs of John Varty's astonishing life, tracking his progression from hunter to film maker to environmentalist.

Weitere Buchempfehlungen

Der weiße Buschmann Peter Stark

Als weißer Buschmann wurde Peter Stark wegen seiner legendären Fähigkeiten im Busch bezeichnet. Dies ist seine Lebensgeschichte als Wilderer und Wildhüter.

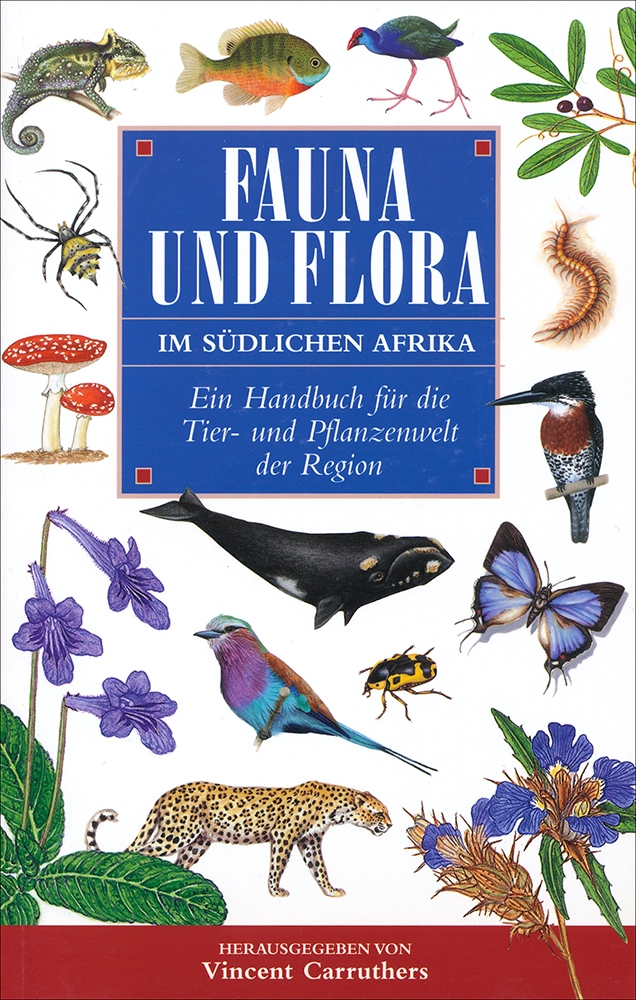

Fauna und Flora im südlichen Afrika

Fauna und Flora im südlichen Afrika: Ein sehr beliebtes Handbuch für die Tier- und Pflanzenwelt der Region.