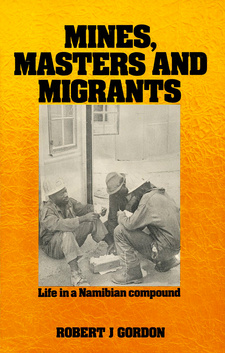

Mines, masters and migrants. Life in a Namibian compound, by Robert J. Gordon

Mines, masters and migrants. Life in a Namibian compound, by Robert J. Gordon. Ravan Press. Johannesburg, South Africa 1977. ISBN 0869750615 / ISBN 0-86975-061-5

Since the epoch-making strike of the contract workers in December 1971 which saw the demise of SWANLA (the South West Africa Native Labor Association), the labor situation in South West Africa (or Namibia) has received a considerable amount of justified attention. Recent studies handicapped by a lack of fresh first-hand data dealing in depth with specific cases. Robert J. Gordon's book Mines, masters and migrants: Life in a Namibian compound, is intended to be a small contribution towards filling this need.

Introduction

Despite the tremendous importance of mines and their attendant compounds for understanding the Southern African economy and hence society, public knowledge about life in mine compounds is minimal. In the fashion of 'good people' engaged in 'dirty work', mine compounds are very much a closed society to the outsider. This book seeks to provide en interpretive description of the condition of the black migrant labor force on a developing Namibian mine and especially its compound. It is based on my experience as a white Personnel Officer, from November 1973 to December 1974 at a mining project near Windhoek, the capital and only city in Namibia. Such an observational situation offers a number of obvious merits and demerits which warrant brief discussion. One important advantage is that the social universe of the mine was small. During my sojourn there, the number of black workers grew from eighty to four hundred. Now in production, the mine has a black work-force of close on two thousand. A mine being brought into production is arguably an 'abnormal' situation and possibly I witnessed 'race relations' at their worst. But this very situation can enrich our understanding of the mine compound complex since it provides an image of life at the Mine before the powerful forces of coercion, so obvious in the Southern African mine compounds, cement themselves into place. While the mine is now physically unrecognisable from the days when I knew it, I believe that the essential social structure and analysis are still valid. My role as a White and a Personnel Officer placed severe restrictions on the nature of the data I collected. I was never formally allowed to undertake research as this would allegedly have impinged on my official duties and moreover have created 'trouble'. Most of the data was thus obtained informally. On the other hand, my official position enabled me to obtain invaluable comparative data on other Namibian and South African mines, and while for ethical reasons I have refrained from incorporating this data into this book, they serve to reaffirm the applicability of these findings for understanding the social life of black Southern African mine-workers in general. Theoretically such a position has respectability for as Gluckman has pointed out

The African newly arrived from his rural home to work on a mine, is first of all a miner (and possibly resembles miners everywhere). Secondarily he is a tribesman; and his adherence to tribalism has to be interpreted in an urban setting. (Gluckman,1961:9)and

if we treat the mine and the tribe as parts of a single field, we see that within all the *reas where it operates, capitalist enterprise produces similar results...What occurs in each area is affected by local variation, and the variant aspects also have to be studies. (Gluckman,1966:223)This work then presents a partial and incomplete perspective. It makes no pretence at objectivity. It is written in what Perrow (1972) has termed the "expose tradition" of sociological writing. My concern for the old-fashioned humanistic ideals of freedom and reason permeate this work. When I reflect on what I learnt while working in the territory then a deep anger wells within me, but at the same time I admire the gutsy determination of the contract workers in overcoming the considerable totalitarian-like impediments they are forced to face. Regrettably I lack the eloquence to portray adequately the pathos of the situation. [...]

This is an excerpt from the study Mines, masters and migrants. Life in a Namibian compound, by Robert J. Gordon.

Title: Mines, masters and migrants

Subtitle: Life in a Namibian compound

Author: Robert J. Gordon

Genre: Social Study

Publisher: Ravan Press

Johannesburg, South Africa 1977

ISBN 0869750615 / ISBN 0-86975-061-5

Original softcover, 15 x 21 cm, 276 pages, some b/w photos

Gordon, Robert J. im Namibiana-Buchangebot

Mines, masters and migrants. Life in a Namibian compound

The study Mines, masters and migrants: Life in a Namibian compound has made black mineworkers situation in the 1970s more visible.

Ethnologists in camouflage. Introducing Apartheid to Namibia

Ethnologists in camouflage: Introducing Apartheid to South West Africa/Namibia from the 1950s.

The Colonising Camera

The Colonising Camera is a pioneering work on photography and the historiographs of Namibia with excellently reproduced photographs.