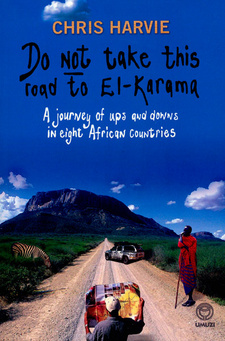

Do NOT Take This Road to El-Karama, by Chris Harvie

Tired of tragic stories, Chris Harvie sets out to see the positive side of the 'Dark Continent' and to enjoy its life and laughter. Do Not Take This Road to El-Karama is the entertaining account of an epic road trip that takes him from his home outside the Kruger National Park to the banks of the Nile in Uganda - and back again. In his haphazard and somewhat eccentric travels, Harvie encounters missionaries and mechanics, locals and ex-pats, rascals and rogues.

[...] The Botswana side of the border, Martin's Drift, has a vast but underutilised paved car park and a hangar-like building that is spacious enough to house a Concorde and contains the largest office in the world, consisting of a counter just under a kilometre long, one customs officer, one immigration officer and enough computers behind a smoked-glass security screen to track Al-Qaeda around a whole hemisphere. Alongside is the smallest office in the world, with four officials collecting road tax and a line of twenty punters trying to get proof of payment from the official clutching the well-thumbed duplicate receipt book. We completed formalities, eschewed the portacabin-based Forex Bureau with its outrageous rates and moved on. Botswana takes its border seriously. There was even a chap on the way out telling us to fasten our safety belts while checking our reflective strips.

Our cars looked like Christmas trees with their endless reflective tape for the various countries we were visiting. At night they were positively dazzling, but we'd done our research and weren't going to be found wanting. Red for Botswana, with additional white in front for Zambia and extra red by the brake lights, yellow for Tanzania down the front, back and sides. In addition, we had extra warning triangles for Tanzania (four) and spare tape to make a V if we were towing. We knew our stuff and were proudly well prepared as we meandered in and out of the donkeys on the road and swerved to avoid the inevitable hornbill that turns right into the car on take-off when the rest of the flock head left into the bush. Avoidance is the better part of valour. Picking their remains out of the roof rack is not a popular task.

The road was good if boring and we pushed on as fast as Mike could go while black clouds reared up ahead and Botswana's black bmw brigade careered past us at twice the speed limit. The tedium of Botswana's roads is relieved only by the unpopular veterinary fences manned by charming, overweight officials, most of whom presumably die an early death from heart disease as a result of the countless kilograms of red meat and boerewors they confiscate in an effort to prevent uncooked livestock crossing into game area - and vice versa - and consume shamelessly at the side of the road, where the braai is always burning.

Botswana has essentially been a huge success since it changed its name from Bechuanaland in 1966 and headed off into the terrifying realms of self-determination under that delightful Sir Seretse Khama and his London-born, white-as-snow wife Ruth. Like every African country, it is a place of contrasts but somehow they are more poignant here. The country hosts three of the richest diamond pipes in the world, discovered, luckily for the Batswana, a year after they achieved independence. One year earlier, arguably, and Britain might never have left. The Botswana government, like that of some of the Gulf states, therefore makes more money than it knows how to spend. The main road north, for example, from Gaborone to Francistown and onwards to the Okavango Delta, is a thousand kilometres of perfect tar and you might see another vehicle every 15 minutes or so. There are only 1.6 million people in Botswana altogether (the smallest population of any country we visited) and very few of them are drivers.

Relative to its neighbours, the country boasts a very low level of urbanisation - the scourge of post-independence Africa's economic balance. Botswana would be a phenomenal success story were it not for the disparity between the lifestyles of these country folk and the city slickers, the furore over the treatment of the San (Bushman) people in the Kalahari and the very high incidence of hiv and aids. Former president Festus Mogae was quoted as saying that he would soon have no nation to lead as all his people were dying. The Batswana are proud, drawn together by Khama Senior (their own post-independence Mandela) to see themselves as one people, regardless of tribe. On previous visits I had always found them a slightly aggressive or at least a rather distant crowd, probably because they have never been very keen on South Africans.

Maybe the white South Africans treated the Batswana with the same disdain they showed for some of their own fellow-citizens in the old days, or perhaps the resentment arises from the fact that South Africans behave as if Botswana were just an extension of their own country. But there has recently been a notable change from both sides. There is, after all, much to be cheerful about in Botswana, with forty years of stable democracy behind it, growth rates of around 12 per cent per year, diamonds, plentiful supplies of gold, copper, nickel and coal, a high standard of health care and good schools. Botswana also has some of the best game-viewing in the world in the Tuli Block and the spectacular Okavango Delta, although it follows the unusual path of promoting premium tourism only and making its national parks expensive and very difficult to reach by car. This again keeps the South Africans out unless they are particularly determined, as we had been on a previous trip, when it took almost a full day to travel the 20 km from the tar road to Nxai Pan - one of the most remote game-viewing areas in the country - only to be told on arrival that Prince Harry had been there for the previous two nights but had flown in by helicopter.

Alexander McCall Smith, in his great series of truly African books, paints with great eloquence the contrasts between the go-getters of the towns and the polite simplicity of life in the bush or the semi-desert. We were sure that we met Mma Precious Ramotswe of the No. 1 Ladies' Detective Agency on several occasions during our short time in Botswana: she filled our car with petrol at two separate garages, she served us in a supermarket and changed some money for us in a bank. And it was tempting indeed to head down to the Tlokweng Road and ask Mr J L B Matekoni, that kind and gentle man, to give the pick-up a quick once-over. I was happy to believe that Mma Ramotswe's Old Botswana way of doing things, with its good manners and high morals, was winning the day and we were feeling welcome. We stopped for the night in Palapye, at the Ithumela campsite, ready to unpack our vehicles for the first time into the first of many open patches of dirt.

This was a dry, dusty town but the campsite offered large trees for shade, unusual open-air flushing loos, with the loo-paper apparently growing on the branches of accompanying thorn trees, and hot showers. It was all we needed and better than we had expected. From every point of view, except the speed at which we were covering the ground, we were like snails. It is fascinatingly easy to compact one's existence from a three-bedroom house, set in ten hectares of open ground interspersed with thorn trees, bougainvillaea and frangipani, into a motorised metal box 4 m by 2 m. Our house was on our back - tents, beds, chairs, a table, cutlery, crockery, coolboxes, stoves, lights, cooking equipment good enough for a nightly bush banquet, not to mention tools, spares, gas, wood, charcoal, sufficient wine and spirits to make a publican green, a filing cabinet full of books and maps, adapters and chargers, cameras, jerry cans, a rain-proof awning, plenty of spare corkscrews and a wide range of Leathermen. We now decanted it all. Before we had set out, there had been a fair amount of competition between the two vehicles, only occasionally spilling over into overt rivalry when one of us thought of something really essential that the other didn t have, like a toaster that fitted on a gas burner, or toothpicks, or an egg-holder. Although we weren't racing, the time had at last come to demonstrate our prowess at getting our tents up in the most efficient manner possible, showing the other vehicle up without making it too obvious. [...]

This is an excerpt from the book: Do NOT Take This Road to El-Karama, by Chris Harvie.

Title: Do NOT Take This Road to El-Karama

Subtitle: A journey of ups and downs in eight African countries

Author: Chris Harvie

Publisher: Randomhouse Struik

Imprint: Umuzi

Cape Town, 2008

ISBN 9781415200643

Softcover, 15x23 cm, 335 pages, several map sketches

Harvie, Chris im Namibiana-Buchangebot

Do NOT Take This Road to El-Karama. A journey of ups and downs in eight African countries

Do NOT Take This Road to El-Karama is an entertaining account of a road journey from Chris Harvie’s home outside the Kruger National Park to eight African countries.

Weitere Buchempfehlungen

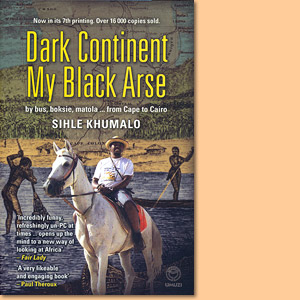

Dark Continent My Black Arse

Dark Continent My Black Arse is a travel writing by an humorous African adventurer who explores and tries to explain his own continent.

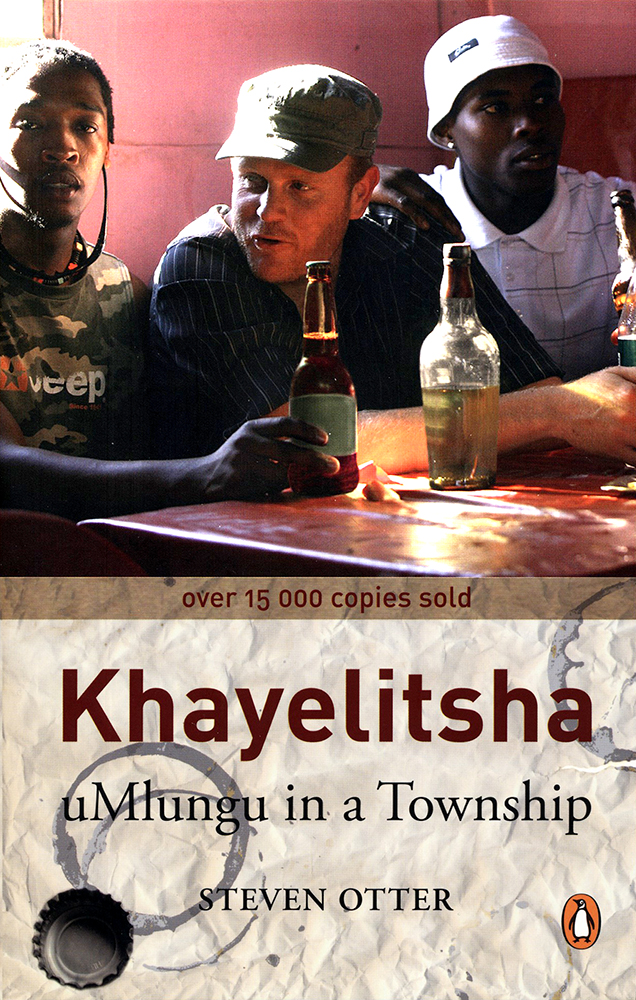

Khayelitsha: A uMlungu in a township

Non fiction: Khayelitsha. A uMlungu in a Township. A white South African makes himself home in a fully black dwelling area outside Cape Town.

Namibia: Eine Reiseerzählung

Trotz abgedroschenem Klappentext ist 'Namibia: Eine Reiseerzählung' ein lesenwerter Reisebericht eines viel und aufmerksam reisenden deutschen Schriftstellers und Juristen.