Creatures of habit. Understanding African animal behaviour, by Peter Apps and Richard du Toit

Example: Communication - signalling and sensing. Without communication there can be no social behaviour, and since mammals are so social it is no surprise that they are also intensely communicative; sending messages that are received through all five of the senses. This extract is about sight.

From our human perspective, communication among other mammals appears to be mostly by visual signalling. During our own daytime activity we see the other mammals that are active in daylight, and to us their signals are obvious and fairly easy to interpret. In fact, with 70 per cent or so of mammal species being small, nocturnal bats and rodents, it is a rather small minority of mammal species in which visual communication has much importance.

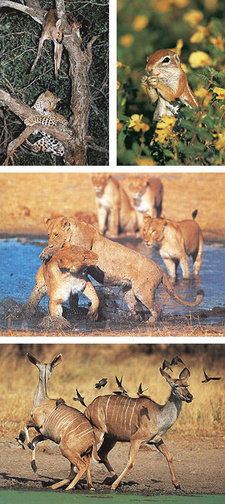

For primates like us, active during the day - the monkeys, baboons and apes - communication by visible signals is more important than it is in any other group of mammals. Their facial expressions can signal all degrees of aggression, fear, contentment, submissiveness, curiosity ... in fact, the whole range of what we recognise in ourselves as emotion (which is not to say that we can conclude as a result that monkeys and apes feel the same emotions that we do). At a more concrete level, the striking contrasts of pattern and colour on monkeys' faces and heads, like the white-rimmed black of a vervet's mask, are unmistakable signals of species identity. A vervet sentinel sitting in a tree sends an all-clear signal just by being there, where the troop can see his bright white undersides. If danger threatens he can give an alarm signal simply by moving away; only if danger appears suddenly and close to his troop will he give an alarm call. A female baboon's swollen pink behind is a signal of sexual receptiveness that can be seen from hundreds of yards away. The pink colour is critical, and obviously depends for its effectiveness on baboons' having colour vision. She supplements her charms by a seductive slow blink that shows her white eyelids.

One of the most striking uses of colour for communication is surely a dominant male vervet monkey's signal of his social rank - a bright red penis set off against the bright blue background of his scrotum. The colour develops at puberty, as testosterone levels rise. It is no coincidence that squirrels are the most brightly coloured rodents and also among the very few that are active during the day. Their long, bushy tails are particularly important in signalling - all the southern African squirrels combine their chattering predator alarm calls with vigorous up-and-down movements of their tails. Tree squirrels also flick their tails while giving the loud chuck-chuck call that advertises their occupation of a territory.

Large antelope that live in open country typically have striking coat patterns. A gemsbok seen from the side is outlined in black, with a black stripe down its cheeks that runs into and accentuates its horns. A sable bull's uniform black coat makes him look bigger to human eyes, and perhaps to other sable bulls that he hopes to dominate. The white on his face and the bright russet on the backs of his ears are in striking contrast to the black, making the angle at which he holds his head and the position of his ears unmistakably obvious. His horns, as well as being lethal weapons, also contribute to visual signalling. A dominant bull stands sideways-on to his opponent, with his tail stuck out stiffly behind, his neck arched, ears cocked, chin tucked in and horns tipped forwards. A subordinate one keeps his tail down, holds his ears back, lowers his head and holds his horns back.

The dark chocolate-brown stripe that separates the cinnamon of a springbok's back from the white of its belly accentuates the stretched and hunched postures that a territorial ram adopts when he urinates and defecates in the middens that mark his territory. During the rut, territorial springbok rams horn the vegetation, sometimes collecting a headdress of greenery. Whether the female springbok that the rams court as they pass through their territories are favourably impressed by these adornments is impossible to tell. Although they are not as strikingly patterned as gemsbok, sable or springbok, other open-country antelope such as tsessebe, red hartebeest and Lichtenstein's hartebeest also use visual signals. Territorial bulls advertise their status, and their occupation of an area, by standing prominently on raised patches of ground, often old termite hills. Similar behaviour is seen in klipspringer rams, which stand prominently on boulders.

Some of the antelope that live in denser habitats also send visual signals. Waterbuck and reedbuck have a pale band across the throat that accentuates the position of a male's chin as he stands with head high in the territorial pose. In all species of spiral-horned antelope - kudu, bushbuck, sitatunga, nyala and eland - there are definite differences between males and females in coat colour. This is most striking in some races of bushbuck where the rams are dark chocolate and the ewes bright russet, and in nyala where the bulls are slate grey and the cows bright chestnut. As they mature, eland and kudu bulls become progressively greyer, especially on the neck.

In an exception which severely proves the rule that it is open-country antelope that make the most use of coat patterns for visual communication, the most colourful and strikingly patterned antelope in southern Africa are nyala bulls, which live in woodland. When a bull is 14 months old he starts to change colour from his chestnut juvenile coat, and by the time he is two years old his flanks are slate grey to dark brown, with up to 14 distinct white stripes across his back and down his flanks, and white spots on his thighs and belly.

His long ears have a reddish tinge on the back. The bottom half of each leg is bright yellow with a dark brown or black band separating this from the colour of his body. He has a mane of long, white-tipped hair running from the top of his head to the root of his tail, and the white tips to the hairs produce a white stripe down his back when the mane lies flat. From below his lower jaw, down the underside of his neck, along his belly and onto the undersides of his thighs there is a fringe of long dark hair.[...]

This is an extract from the book: Creatures of habit. Understanding African animal behaviour, by Peter Apps and Richard du Toit.

Book title: Creatures of habit. Understanding African animal behaviour

Authors: Peter Apps; Richard du Toit

Struik Publishers

Cape Town, South Africa 2006

ISBN 9781770073920

Softcover, 27x27 cm, 160 pages, throughout illustrated

Apps, Peter und du Toit, Richard im Namibiana-Buchangebot

Creatures of habit. Understanding African animal behaviour

Creatures of Habit explaines the habit of Africa animals and helps to understand their behaviour.

Catching the Moment: Photographing Wildlife In a Timeless Wilderness

In Catching the Moment: Photographing Wildlife In a Timeless Wilderness, the photographers share a wealth of advice and useful information on how they captured the images in Botswana.

Africa's Big Five

The authors of Africa's Big Five present experiences and insights they have gained through years of close observation.

My first book of southern African mammals

My First Book of Southern African Mammals introduces a cross-section of 58 animals.

My first book of Southern African wildlife

My first book of Southern African wildlife introduces children to 58 mammals, 58 birds and 56 reptiles.

Wild Ways: Field companion to the behaviour of southern African mammals

Wild ways, field companion to the behaviour of mammals, explains how animals in Southern Africa behave and why they do so.

Smithers' Mammals of Southern Africa

Smithers’ Mammals is an authoritative and popular guide to the mammals of Southern Africa: Fully revised & updated edition.

Fauna und Flora im südlichen Afrika

Fauna und Flora im südlichen Afrika: Ein sehr beliebtes Handbuch für die Tier- und Pflanzenwelt der Region.