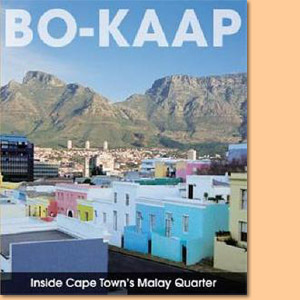

Bo-Kaap - Inside Cape Town’s Malay Quarter, by Astrid Kragolsen-Kille and Robyn Wilkinson

Inside Cape Town’s Malay Quarter captures the essence of the vibrant and historical Bo-Kaap district and is written and photographed by Astrid Kragolsen-Kille and Robyn Wilkinson.

Robyn Wilkinson Astrid Kragolsen-Kille

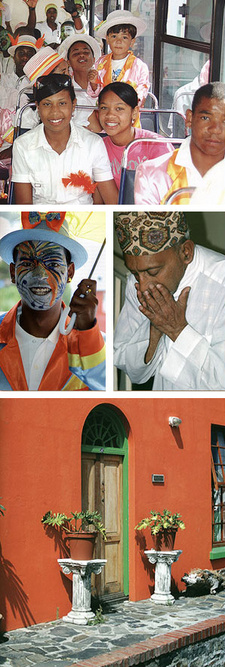

Like bundles of unopened letters, stories lurk on every corner of historical, colourful Bo-Kaap. Pause on any of the cobbled streets for long enough and sooner or later you will be enriched by tales of days gone by. In the rows of picturesque houses there is almost always someone at home, most probably an auntie or granny. If for some reason the house is empty, the neighbour will certainly know where the residents are. There is a strong culture of knowing everyone’s business; gossip is traded openly and freely; news and concerns are shared. Everyone is everyone else’s auntie, uncle or cousin, whether they are related or not, and one person’s issue is everybody’s business. Life happens on the pavements outside the brightly coloured houses and continues late into the night. Children’s impromptu ball games are set up on the street and only briefly interrupted when a car turns into the street. Like a well-rehearsed production, and to shouted instructions from mothers, aunties and grannies, toddlers are snatched up by older siblings until the car has driven past and the game can be resumed. Often the car has to slow down or stop and wait for the children to be moved. Above the sounds of children playing, parents scolding, and the familiar asalaam alaikum greeting (peace be with you in the name of Allah), is the call to prayer emanating from the nearest of the seven active mosques in the Bo-Kaap. The deep drone serves as a soothing chant for the enlightened, an irritant for the compromised conscience and, for the uninitiated, a reminder to acknowledge spirituality. The community has a way of bringing everybody into line. It also has a way of caring for their members. Local resident Somaya Salie explains that, with eight children, she wouldn’t have been able to afford the nannies she would have needed had she lived anywhere else. In the Bo-Kaap everyone carries the responsibility of parenting. She can let her children wander around the neighbourhood, knowing they will be disciplined, cared for and fed if necessary.

When a woman’s husband is away overnight, someone will send a son to stay over. Parcels of food and medicine are shunted from door to door, depending on need. Dedication to Islam ensures common values and morals; ever-watchful elders consider it a duty to dish out reproaches. Suspected adulterers, party animals and students playing hookey are challenged and made accountable. Everyone knows who makes the best koesisters, the softest rotis or most delicious curry. Tradesmen working late into the night can be sure of being fed by their neighbours. Community spirit and neighbourly concern is part and parcel of the lifestyle. Knock on anyone’s door and they will invite you in before asking your business. Only after you’ve been settled in with a cup of tea, will they ask the reason for your visit. ‘Our religion requires us to be hospitable to our neighbours and never to turn anyone away,’ explains resident Hadija. On-going celebrations and traditions ripple through the community in different degrees of excitement. There is always a household preparing for a wedding, birth, naming ceremony or other milestone event.

Artists and bohemians have long been inspired by the exotic smells of cooking and incense, sounds of Arabic chants, the gossip and visual stimulation of the brightly coloured houses. Perhaps they also sense the spirit of the place created by the apartheid struggle when resolve was high and secrets were kept, poems written and plots were hatched. They aren’t the only ones drawn to the area. Investors are also attracted by the Dutch and Georgian styled houses built in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Families with houses that have been passed down through generations are concerned that the charm and beauty of the area will be lost to people unaccustomed to Malay tradition. Sons and daughters of the older Malays are tempted by the high prices the houses are getting to sell up and move to bigger houses in less expensive areas.

There are mixed feelings about the dilemma of improving financial circumstances at the expense of losing a cherished tradition. ‘A treasured piece of living history is being replaced by gentrification, says local resident, Kadija. Another resident, Fatima, is saddened by the fact that crime and problems with drugs have made us keep our doors locked. Up until very recently, our doors were always open. Now we have the added problems of new people coming into the area, some of them drinking alcohol on the pavements and, would you believe it, even complaining about the „noise“ of the muezzin (call to prayer).’ As the value of these properties increases, so do rates and taxes, contributing to the pressure to sell. We wanted to capture something of the essence of this beautiful and historical area before it changes. Cape Malays are testament to a living history and take pride of place in Cape Town’s heritage.

This is an excerpt from the book: Bo-Kaap - Inside Cape Town’s Malay Quarter, by Astrid Kragolsen-Kille and Robyn Wilkinson.

Title: Bo-Kaap. Inside Cape Town’s Malay Quarter

Authors: Astrid Kragolsen-Kille; Robyn Wilkinson

Struik Publishers

Cape Town, 2006

ISBN 9781770072817

Paperback, 21x25 cm, 160 pages, throughout colour photos

Kragolsen-Kille, Astrid und Wilkinson, Robyn im Namibiana-Buchangebot

Bo-Kaap - Inside Cape Town’s Malay Quarter

Inside Cape Town’s Malay Quarter captures the essence of the vibrant and historical Bo-Kaap district.