A game ranger remembers, by Bruce Bryden

Bruce Bryden was a South African game ranger and wrote his best selling memoirs after retirement.

I spent 30 of my best years - from 1971 to 2001 - as a nature conservation officer with South African National Parks. Of these, all but three were devoted to the Kruger National Park, that great and justly famous sanctuary for the animals of southern Africa that have been so grievously sinned against by mankind. The retreat of the game herds and the shrinking of their habitats is a matter beyond pity or regret; in the end, as it is everywhere in the world, it is part of a greater cycle of change that is driven by the struggle for resources (not unmixed, of course, with depredations inspired by sheer greed, and compounded by silly or short-sighted actions), and inevitably the animals have lost, so that they have become prisoners in the land where once they teemed in great numbers almost wherever the eye could see. But game reserves like the Kruger National Park and many others have ensured that although a relatively pristine southern Africa has disappeared, most likely for ever, most of the veld creatures in all their enormous diversity have survived, although there have been a few grievous losses along the way, among them the bloubok, the black-maned Cape lion (although I don't really believe that it was a different species from our common lion) and perhaps the quagga. The quagga might still be dragged back from oblivion by a re-breeding programme that is currently in progress, but generally speaking, the species that have gone are gone forever.

That is primarily why the game reserves exist. It is not the only reason - they are invaluable to scientific research, for example, and can make significant contributions towards social upliftment by way of direct employment, or indirect employment as a result of tourism - but at the end of the day they are first and foremost safe havens for the 'first people’ of the bushveld, and open-air classrooms where human beings can renew the ancient interaction between man and animal that has progressively disappeared in an increasingly overpopulated and technologically advanced world.

That is why I said that I had 'devoted' almost my entire career to the Kruger National Park. Dedicated game rangers do not, frankly, gain any noteworthy material reward from their arduous, usually under-funded and frequently dangerous work, but when the time comes for them to hang up their well-worn boots they have the satisfaction of knowing that although they might not be remembered by name to future generations, those generations will reap the benefit of their efforts.

When I became Chief Ranger in 1983 the Kruger National Park was on the threshold of an immensely significant period in its history. It was then almost a century old, and it had developed to a state that would have surprised the pioneers like James Stevenson-Hamilton and Harry Wolhuter, who had nursed it into life and guided it through its perilous infancy to the beginning of more enlightened times. When the Park was proclaimed by President Paul Kruger, attitudes toward wild animals were still based on a very literal interpretation of the biblical injunction that God had given Man dominion over the birds of the air and the fishes of the sea. By the time the pioneers bowed out the world was coming to realise that such dominion meant not the conferral of a licence to plunder but the assumption of a great and noble responsibility.

Now, at the dawn of the 1980s, the Kruger National Park was about to go through another great - if vastly different -transition period, a time of immense social and political change, protracted civil warfare, widespread population movement and great want. We were lucky enough to be the midwives during that period - I say 'we' because the hands of many men and women contributed to the task. They came from a variety of backgrounds, walks of life and cultures. Some were black, some were white, and between them they worshipped a variety of different deities and spoke half a dozen different languages. A few went bad in the process and betrayed their trust. Most of them did not, and when they retired they handed their successors a going and even flourishing concern.

In those 27 years in the Kruger National Park I served at every level, starting as a humble but rather grandiosely titled Tost-Graduate Assistant Biologist' and working my way up to Ranger, Chief Ranger and finally to Senior Manager: Conservation Support Services. Every step up the ladder exposed me to new experiences and new insights, all gained the hard way, so that my personal conservation ethic was in a constant state of development and maturation as I did things under my own steam and benefited from the influence and mentoring of various individuals I encountered or worked with. Formal education is a vital part of the modern game ranger's professional repertoire, but book-knowledge is useless without a sound leavening of experience - both personal and the kind that can be gained only by listening to those wiser than yourself.

I wrote this book partly at the urging of various friends and colleagues. I might not have undertaken the task except that so many of my contemporaries and near-contemporaries had promised to do the same but had never actually got around to the task. To me it has always seemed such a terrible waste that those life experiences - an enormously varied and often unique body of knowledge - should be allowed simply to evaporate instead of being shared with people not fortunate enough to have acquired them. So I decided to spend a year writing down some of my memories.

This is an extract from the book: A game ranger remembers, by Bruce Bryden.

Book title: A game ranger remembers

Author: Bruce Bryden

Publisher: Jonathan Ball

Cape Town, South Africa 2005

ISBN 978-1-86842-315-6

Softcover, 13x19 cm, 408 pages, several b/w photos

Bryden, Bruce im Namibiana-Buchangebot

A game ranger remembers

A game ranger remembers a collection of stories about the life of men and women who guard the Kruger National Park in South Africa.

Weitere Buchempfehlungen

Mary Elizabeth Barber: Growing Wild. The Correspondence of a Pioneering Woman Naturalist from the Cape

A biographical study: Mary Elizabeth Barber: Growing Wild. The Correspondence of a Pioneering Woman Naturalist from the Cape.

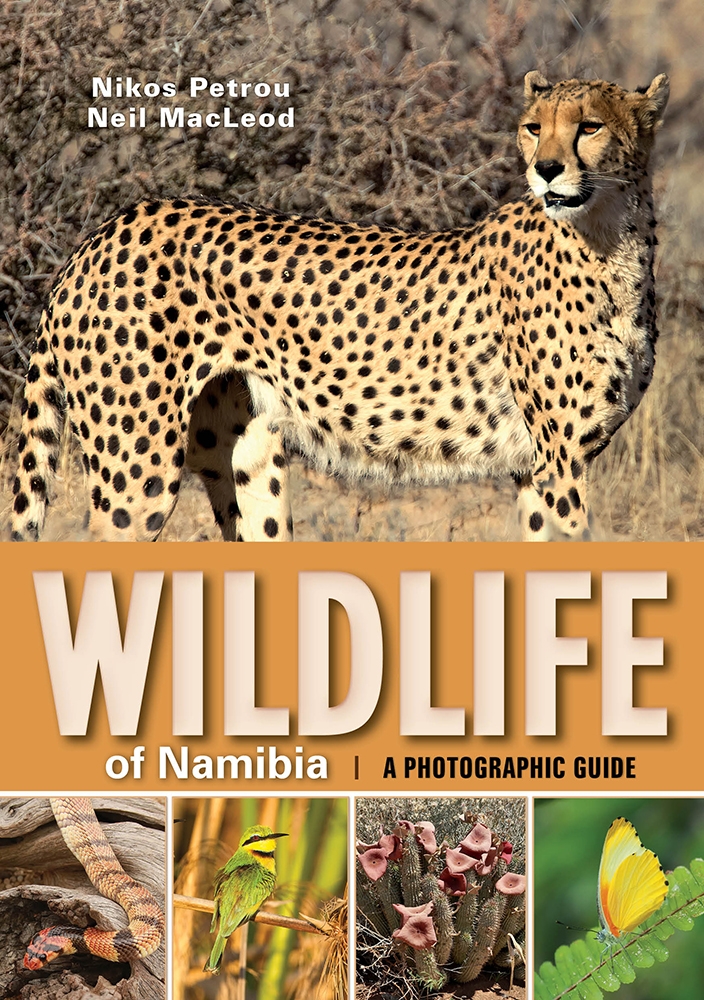

Wildlife of Namibia: A Photographic Guide

Wildlife of Namibia is an easy-to-use guide to Namibia’s most conspicuous and interesting mammals, birds, reptiles, invertebrates and plants.

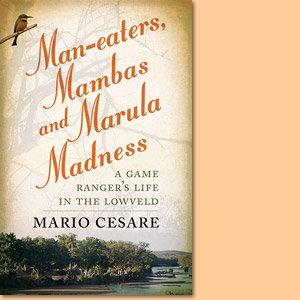

Man-eaters, mambas and marula madness: A game ranger's life in the Lowveld

Mario Cesare, in man-eaters, mambas and marula madness, decribes his life as a game ranger in the Lowveld region.